Food

A Brief History of School Lunch: Part 1 - Looking Back

Philadelphia starts a hot lunch program for the price of a penny. Prior to this, children typically brought cold sandwiches with them from home.

The Women’s School Alliance of Wisconsin starts serving hot soup and rolls at schools in Milwaukee.

The Women’s Educational and Industrial Union starts serving hot lunches at high schools in Boston.

"The teachers [in Boston] are unanimous in the belief that the luncheons are helping the children both physically and mentally. They are more attentive and interested in the lessons during the last hour of the morning and the result in their recitations gives the proof."

- An excerpt from the 1910 Journal of Home Economics

The New Deal provides the first federal aid for school meals in 1932 as loans to cover staffing costs. By 1934, federal aid covers the employment of 7,442 women who cook and serve school food. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) seeks markets for excess American farm products like pork, dairy, and wheat, and offers them to schools. In 1939, 14,075 schools with 892,259 students participated in the federal program, rising to 5 million students in 78,841 schools in 1942. (USDA)

President Harry Truman signs the National School Lunch Act. Meals are offered free or at a reduced cost for those who cannot pay.

The Child Nutrition Act adds school milk and breakfast programs and moves the National School Lunch Program to the USDA.

Ketchup is declared a vegetable. President Ronald Reagan downsizes portions and reduces the number of youth who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act passes Congress, calling for smaller portions, more fruits and vegetables, lower sodium levels, more whole grains, and flavored milks that are fat-free. It’s enacted in 2012.

Congress declares pizza a vegetable.

Sonny Perdue is appointed secretary of agriculture for the USDA. Higher-fat chocolate milk is reinstated.

"I wouldn’t be as big as I am today without chocolate milk."

- Sonny Perdue

Few of us are lucky enough to recall from-scratch school lunches cooked within the cafeteria walls. For many of us, the term “school lunch” brings memories of soggy mass-produced French toast sticks on plastic trays. My personal favorite was Salisbury steak smothered in gravy. As school lunch became politicized, nutrition was placed in the hands of large food companies. A gallant few lead today’s school lunch revolution working to put from-scratch food back on the menu.

A Solution for Every Problem

School lunches at the turn of the 20th century were considered to provide not only nutrition, but teach healthy habits. Most were spearheaded by women-run, local nonprofit organizations (Time).

But what started as a goodwill effort to provide meals for better learning and growing turned into a way to save commodity farms during the Great Depression. Federal subsidies for beef, pork, and dairy led to overproduction that could not be sold in markets, so the government bought it and gave it to schools.

After men who suffered from malnutrition were excluded from enlisting in World War II, military leaders sought a way to ensure high caloric intake in case of an impending threat from the Soviet Union. They convinced President Harry Truman to sign the National School Lunch Act in 1946 to “safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children.” The focus on calorie-dense meals continued into the 1980s and ’90s. Ironically, today, one-quarter of America’s youth are too overweight to serve in the military (Healthy Schools Campaign). The National School Lunch Act solidified the National School Lunch program as a permanent part of schools.

School Lunch Requirements

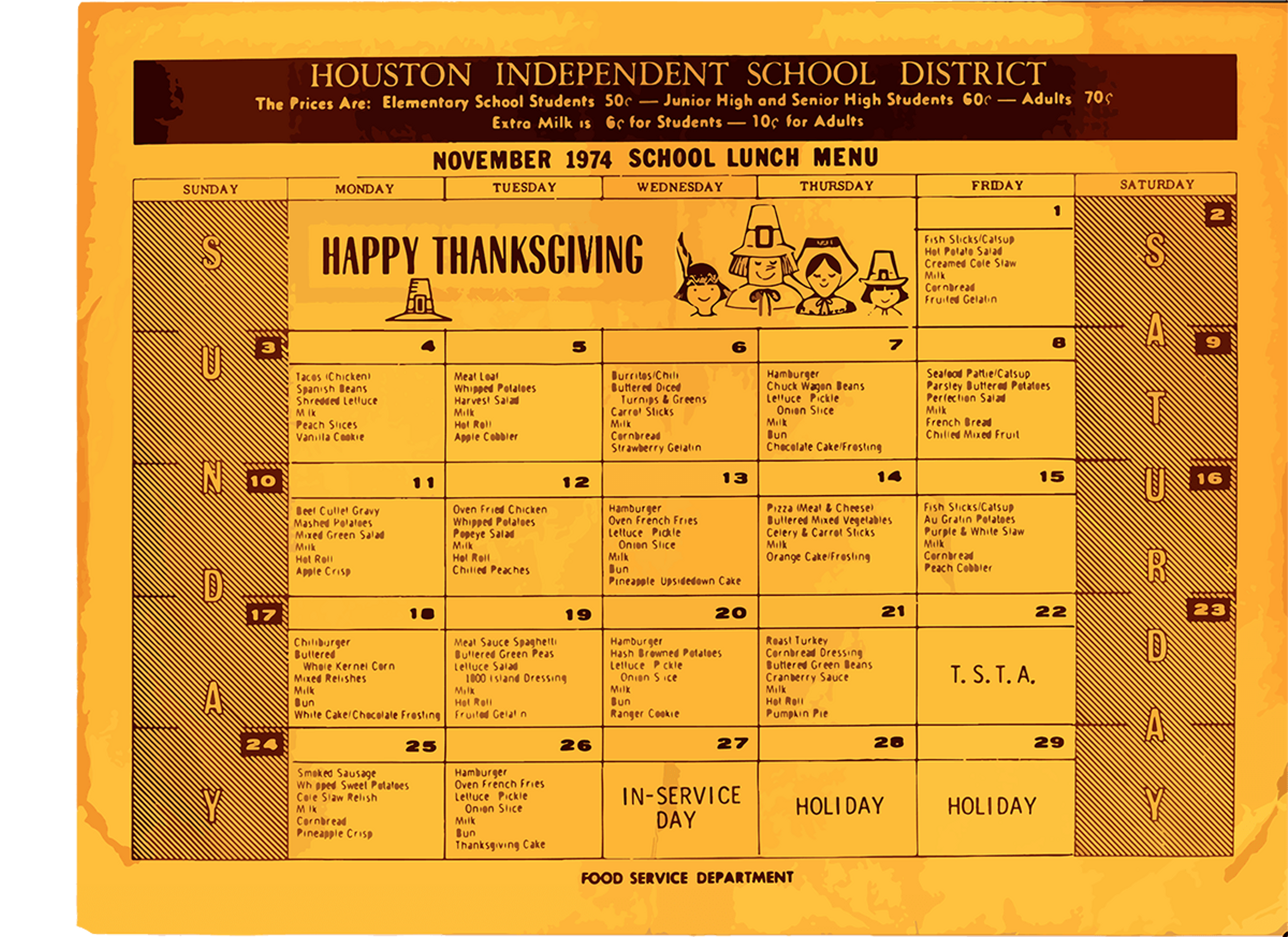

To accept food donations and get reimbursed for serving meals, schools must meet certain nutritional requirements. The meal requirements were split into different types, depending on the kitchen space available to make meals. Most schools in the 1940s did not have enough space to cook. Below are sample lunches for schools with full kitchens and schools with limited kitchens.

1946 Meal Requirements for 10- to 12-year-olds. (Source: “The National School Lunch Program: Background and Development” by Gordon W. Gunderson)

Today’s lunches must include five components: fruit, vegetables, grains, meat, and milk. They are typically 550 to 650 calories with:

- 30% or fewer calories coming from fat (less than 10% from saturated fat).

- One-third of the recommended dietary allowances for protein, vitamins A and C, iron, calcium, and calories. Sugar is not regulated.

- Water as a beverage option (previously only milk). Milk is either non-fat flavored or 1% white.

Heat and Serve Limitations

By the 1960s and ’70s, most cooking and preparing was happening in central district kitchens. This led to the assembly-line-type meal production common in most districts today, with meals prepared centrally and sent out to schools in plastic-wrapped heat-and-serve trays. Food workers with shifts of one to three hours unwrap and reheat the meals and serve them to kids. School kitchens today often lack the appliances or space to do anything other than reheat meals.

“Big Food” on the Menu

Alice Waters described the school lunch program as a “junk-food distribution system” in the 2000s (NY Times). In 2003, the USDA spent nearly a billion dollars on food for school lunches.

Multinational food companies (Big Food) are the main beneficiaries when meat, dairy, and frozen vegetables are purchased for school lunches (frac.org). Big Food also regularly funds the School Nutrition Association, the national organization for food service workers. In 2018, these companies gave around $24,999 each to the School Nutrition Association’s annual conference: Domino’s Pizza, General Mills, PepsiCo, and Land O’Lakes. Other brands like Cheez-It, Campbell’s, and Schwan’s (makers of Tony’s and Red Baron pizza) lined the conference’s annual exhibit hall. Their infiltration and influence make it difficult for school lunch reform to happen.

Michelle Obama tried fighting Big Food’s hold on the school lunch program. In a 2010 speech to the Grocery Manufacturers Association, the Big Food lobby, she stated, “We need you not just to tweak around the edges, but to entirely rethink the products that you’re offering, the information that you provide about these products, and how you market those products to our children. That starts with revamping or ramping up your efforts to reformulate your products, particularly those aimed at kids so that they have less fat, salt, and sugar, and more of the nutrients that our kids need” (Think Progress).

The Let’s Move campaign shifted from prioritizing healthy food in 2010 to physical activity in 2013. Behind the scenes, money from major food and beverage companies poured in. According to Reuters, 50 food lobbies spent more than $175 million in President Barack Obama’s first three years in office, over double the $83 million spent in the final three years of the Bush administration (Reuters).

Even the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, passed by Congress in 2010, could not combat Big Food’s influence. The potato lobby successfully opposed limits on “starchy vegetables,” aka French fries and potato chips (Bloomberg). Potatoes remain the top-selling vegetable in the United States by weight (USDA), followed by tomatoes, which are used in pizza sauce.

The Taste War: Changing Palates

Obama-era regulations on grains and fat led to whole-wheat pitas and fat-free flavored milk that divided a nation. On one side were school lunch reform proponents like Michelle Obama, the American Heart Association, and the American Medical Association. On the other side were big food companies and Instagram-savvy teens posting food they deemed inedible with the hashtag #ThanksMichelleObama.

Nearly 2 million kids nationwide started throwing food away and then bringing their own lunches, resulting in lost revenue of about $3.31 per plate (Bloomberg). The St. Charles Parish Public Schools outside of New Orleans said about 500 of 4,500 kids stopped eating school breakfasts, blaming whole-grain biscuits. A high school in York, Pennsylvania, reportedly sold only 15 hamburgers instead of 300 in a day because they were on a whole-grain pita rather than a classic white bun (Bloomberg).

Unhappy School Nutrition Association members and Perdue’s appointment to secretary of agriculture in 2017 obliterated Obama-era sodium regulations, avoiding the so-called “cheese apocalypse,” or a world of school lunch with no cheese. Whole-grain targets were stymied, and higher-fat chocolate milk was reinstated. (Bloomberg).

According to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, undoing the Obama-era regulations means “the difference in sodium consumption for high schoolers will be the equivalent of almost two Big Macs a week” by 2022.

Children in South Carolina take a midmorning lunch in 1939. Source: Library of Congress | A typical school lunch in 1966. Source: Getty Images Underwood Archives, Time Magazine.

Price, Price, Price

Federal reimbursement, an average of $2.50 per lunch, must also cover things like staff benefits, janitorial services, and heating. That leaves far less than $2.50 for the actual food and food preparation.

“Right now, we have a school food program that’s cash-strapped, where a lot of the focus is on cheapness,” says Dr. Jennifer Gaddis, an assistant professor of Civil Society and Community Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and author of The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools. “It’s based on pricing—find the most scientifically nutritious food for the cheapest price. Within that model, what sort of food jobs do we end up supporting?”

Hope for the Future

Although school lunch programs have been fraught with underfunding, competing agendas, and politicization, there are programs offering hope for the future of our children’s school meal programs. In particular, the farm to school and from-scratch cooking movements are striving to improve the flavor, quality, and sourcing of the food on kids’ lunch trays.

Want to learn more about these positive developments? Read the rest of the story in Part 2 of a Brief History of School Lunch: Moving Forward.

Hannah Wente has her Master's in Public Health from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is a health communications professional by day and freelance writer by night. Her favorite second breakfast is a strata made with pasture-raised eggs and bits of focaccia.

Related Articles

- Tags:

- innovation