Rooted

The Sioux Chef: Cooking with Wild Foods & "Cool Heirloom Crops"

Sean Sherman, founder, CEO and chef at The Sioux Chef, is a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe. Sean was born in Pine Ridge, South Dakota and has been cooking in Minnesota, South Dakota and Montana for the last 27 years. While his work in the restaurant and food industry began out of necessity—a teenager who needed a job—it grew into a passion. In recent years Sean’s main culinary focus has been on revitalizing indigenous food systems in a modern culinary context.

In 2014, he opened The Sioux Chef as a caterer and food educator in the Minneapolis/Saint Paul area. In 2015, he added the Tatanka Truck, a food truck that serves indigenous foods of the Dakota and Minnesota territories, and he has plans to open a full-out restaurant in the near future. Chef Sean and his vision of modern indigenous foods have been featured in many articles and radio shows, along with dinners at the James Beard Foundation in Milan and also Slow Foods Indigenous Terra Madre in India.

“I got to a point where I realized that I was learning about all these other cultures and I really didn’t know much about the culture that I was born into,” says Sean of his formal training as a chef. This curiosity made The Sioux Chef what it is today. Sean speaks of food-related illnesses like diabetes and obesity that are prevalent in Native American communities. He believes widespread revival of ancestral culinary traditions would drastically improve health in indigenous populations and beyond.

“Before indigenous peoples were pushed onto commodity programs, they didn’t have a lot of these health issues because they were eating a lot of really extremely healthy wild foods and they were growing lots of cool heirloom crops,” says Sean. Today he incorporates these wild foods and heirloom crops into the menu at The Sioux Chef. Using cattails in recipes? Brewing cedar maple tea? All in a day’s work for Sean and his team. They only use ingredients that were in use prior to settler colonization. This means no wheat flour, processed sugar, dairy or even beef, chicken or pork in their cuisine. Instead they offer wild game, wild rice, tubers, cornmeal and other foods that were traditionally foraged in the Dakotas and Minnesota.

Sean says he and his team are “testing the limits of what we can do with what’s around us, and looking at how simply people processed foods and how unique that was. Our work is not only working with the tribes, but giving people a deeper understanding of the land that they’re standing on, because all of this was indigenous land at one point.”

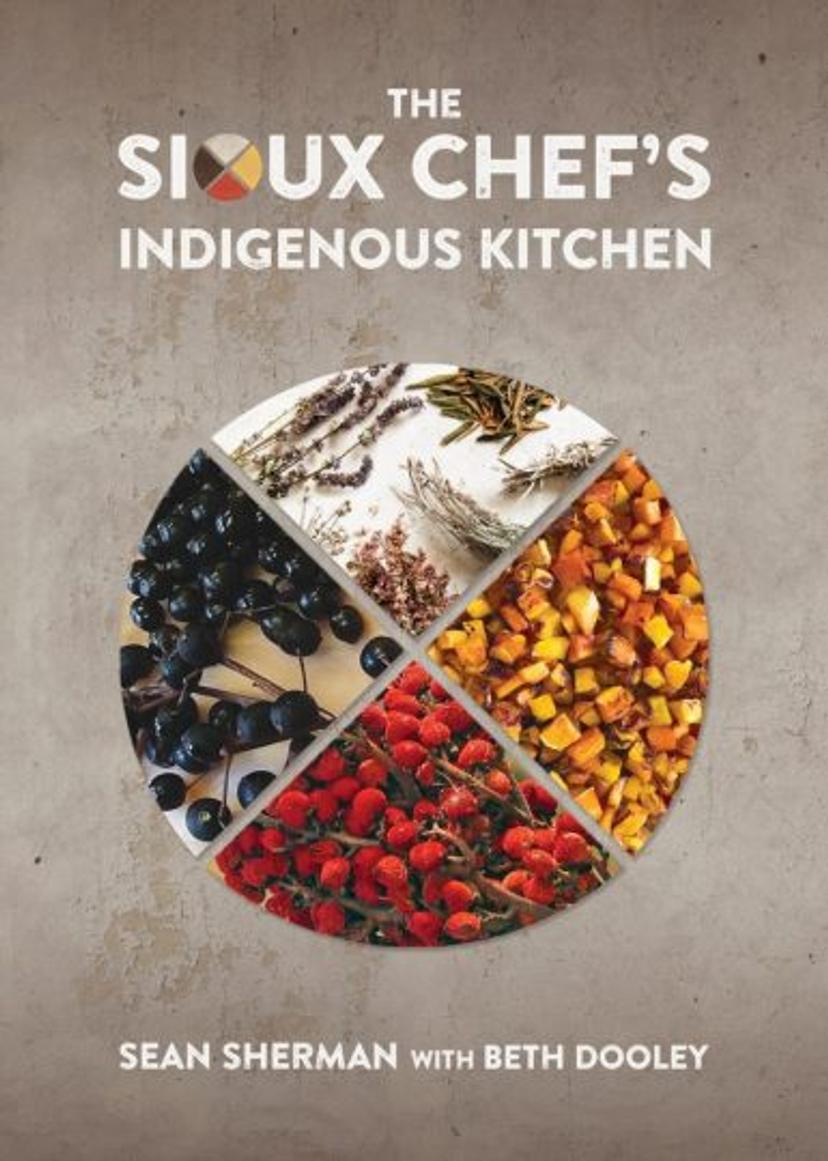

He has co-written a cookbook called “The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen,” which contains many of his indigenous recipes. The book will be released in October of this year, and can be pre-ordered now through the University of Minnesota Press.

Understand the land you stand on better by listening at the link below, on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play or wherever you get your podcasts.

Welcome to Rootstock Radio. Join us as host Theresa Marquez talks to leaders from the Good Food movement about food, farming, and our global future. Rootstock Radio—propagating a healthy planet. Now, here’s host Theresa Marquez.

THERESA MARQUEZ: Hello, and welcome to Rootstock Radio. I’m Theresa Marquez, and I’m here with Sean Sherman, who is Oglala Lakota and founder and CEO of Sioux Chef. Welcome, Sean!

SEAN SHERMAN: Thank you for having me.

TM: I’m so honored to have you. Sioux Chef means that you’re from the Sioux tribe.

SS: Yep, I grew up on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, so we’re all part of the Oglala Lakota Sioux tribe in that area, where I grew up. And so I just utilized it kind of as a play on words, where you’ve got, you know, working in the kitchens and having sous chefs, and then creating a “Sioux” with S-I-O-U-X chef.

TM: I think that’s so clever. And also, gee, you’re all the way from Dakota, but now you’re in Minneapolis. And you are going to be opening a restaurant, I understand, there soon. Or it that open already?

SS: Nope, it’s not open yet, but we are working hard trying to find the location so we can move forward with building it out. But we have lots of big plans for that scenario.

TM: Well, I’m thrilled. And I’m just so excited about what you’re doing. It sounds to me like you’re very familiar about the kind of food that’s on the reservation. And I read that you were hoping to go back in time, so to speak, and look at some of the foods that the Native Americans did eat prior to commodity food.

SS: Yeah, you know, so I grew up in Pine Ridge Reservation, which in itself has been a pretty oppressed area for such a long time. And as a chef, I had worked with many different cultures. I had learned Spanish food, French food, and all sorts of European and African foods, Indonesian, Asian, in general, just Japanese. So whatever my interest was, I’d been learning all these different foods and then working with local farms and utilizing a lot of really super-fresh products constantly in my chef career. And then I got to a point where I realized that I was learning all these other cultures and I really didn’t know much about the culture that I was born into, when it came to the food system side of it.

So I started really trying to research what is Native American food and utilizing understanding of that. Because when I grew up, we did grow up with a lot of commodity foods because there was a lot of very poor communities there and there was a lot of government subsidies—which there always has been for a long time. But we look at these commodity food programs for these people that struggle with a lot of health issues, like Type 2 diabetes and obesity and heart disease, and there’s a huge list of kind of foodborne illnesses out there. And a lot of it stems from having to survive off of these really not very healthy, but foods that you can survive on but they don’t do you a lot of good, because they’re high in fats, they’re high in sugars, they’re high in salts, they’re highly processed.

And so we just wanted to try to get people to rethink about what their traditional food systems were, because before indigenous people were pushed onto commodity programs, they didn’t have a lot of these health issues because they were eating a lot of really extremely healthy wild foods and they were growing lots of cool heirloom crops that had been…you know, agricultural scenes of Native Americans have been going on for thousands of years, so there’s all sorts of cool seeds still out there. And there was just this rich diet of all sorts of vegetable variation and wild protein, and it was just really, really healthy. So it was this awesome low glycemic diet that people were able to survive from. So we want to combat that by—through knowledge mostly.

TM: Wow, that’s so fantastic. And even though you’re saying it’s on Pine Ridge and other Indian reservations, it’s pervasive throughout the American diet as well. For those of you out there who would like to learn more about some of the things, there’s a great link, Sioux-chef.com/about, which you can learn more about Sean Sherman and a wonderful New York Times, several articles that show some of the foraging that you’ve done. So part of what you’re doing is you’re taking a look at things were already out there that use to be foraged that were very healthy for you. I wonder if you could talk about that a little bit.

SS: Yeah, so looking at, for us, just understanding what makes up an indigenous food system, the ethnobotany and wild food side of it is a big part of it. So just understanding all the plants and being really connected with nature is a commonality that most indigenous cultures around the world have, because they’re really resourceful about things that are directly surrounding them, and knowledgeable too. So it’s just looking at all these plants that are constantly around us and knowing the true value of everything, because most plants were either food, medicine, or utilitarian of some sorts—where you can make dyes and ropes and clothing, things like that, other things. And a lot of the time plants have all three of those properties.

So we just kind of took the time to not call everything a weed if we didn’t know what it was, but to take the time to learn the name of it and its true nature and what we can do with it. And looking at past cultures and how they utilized things, because the wild plants around us, for indigenous communities, were food and all the medicine and everything. People were extremely knowledgeable. So we utilize a lot of that nature—still recovering and understanding a lot of that knowledge to utilize for the foods that we do. So we make things like cedar maple tea, or we’ll utilize cattails, or even non-indigenous species like dandelions and burdock and things like that—they’re still food. So we look at those plants through an indigenous perspective and see they have use. So we want to utilize a lot of those plants for the work that we do.

TM: Wow, exciting. And I know that dandelions are supposed to be very, very healthy for you. But I have to admit that’s a pretty exciting list of foods. We certainly learned from Paul DeMain a couple weeks ago when we interviewed him that there’s a rich history of Native American cooking and food. And the kind of health that Native Americans had before the commodity programs was excellent. I am so interested in your passion for this kind of food and for food in general, Sean. And I’m wondering if we could back up a little bit, and what made you get passionate about food?

SS: Well, I think food is something that, as humans, we all have in common, right? I think part of it, for me, in my career as a chef, I started working in restaurants basically as soon as I could work. So my mom moved us off Pine Ridge reservation right before I started high school. We moved to small community in South Dakota called Spearfish, South Dakota, which is on the northern edge of the Black Hills and right along the border of Wyoming. And I just started working in tourist restaurants as soon as I could. So I was 13 when I started working in restaurants. And it was mostly just, kind of out of necessity because we were poor and I needed to work and make some money. And I was able to, so I just started working young and worked all through high school and college. And so after college I moved to Minneapolis and just kind of shot my way up the ranks since I already had a lot of skills.

But yeah, food’s always kind of been a large part of it. And food is something that just brings us all together, whether we’re families or communities, by having big feasts and gatherings, and, you know, something that’s just really important. And my chef career has just been able to develop with kind of the unique path it took.

TM: I’ve seen that you’ve been in summits. I got so excited when I heard about the Great Lakes Intertribal Food Summit, bringing so many different Native American tribes together to look at how we’re eating. How has it been? Do you think that there are things that are moving right now on how you’re going to redefine Native American foods for all the tribes?

SS: Yeah, and I think we’re doing more than just redefining foods for tribes, but we’re really looking at North America as a whole and looking at all of its indigenous culture and history. So a lot of the talks that I do I have to break it to people that there’s a lot more history back there that starts before Laura Ingalls here in Minnesota, you know, that we just don’t… People don’t learn a lot about the history before European settlers come in, and that’s kind of where history books start, but there’s so much to learn. So we’re really kind of starting to redefine what North American food is in general, because when you look at the indigenous cultures, every few hundred miles you go across the nation, it changes with culture and language and food systems and everything. So it’s extremely diverse. And we feel the understanding of indigenous foods will help people really understand that diversification and that variety that’s out there.

So instead of just having hamburgers and French fries and craft beer at every stop you make if you drive across North America, or poutine in Canada, you’ll realize that there’s so much more to offer because every region is slightly unique and there’s so many different cultures, and there’s so many different foods out there and so many different histories. And understanding the indigenous backbone of the Americas really kind of helps you understand that through food. And food is something that’s so tangible for people. So I think people get it easier because it’s something that we can still have today and it’s something that really speaks to people.

So our work is really not only working with the tribes but just showcasing people a deeper understanding of the land that they’re standing on, because all of this was indigenous land at some point. And we just want people to just understand there’s so much to learn from the past that we can utilize for the future.

(10:50)

TM: Do you know, is there anyone who’s writing books now about some of this wonderful history? There must be some more information that people can get of some of that very rich culture of the food that was around us and how it got integrated into the kind of farming that we were doing—this whole wild harvesting as well as actual cultivating.

SS: Yeah, there’s a lot of great books on indigenous food and culture here today. And we have our first cookbook coming out at the end of this year in October, so actually it’s just a few months away at this point. But we’re really exploring with the way we do it by utilizing only indigenous ingredients to create something unique for the modern era that really reflects on the past. We kind of maintained and hold onto a lot of the cultures and beliefs of those food systems and of people that lived before us. And for me, it’s just going backwards and trying to understand the foods of my direct ancestors, starting at my great grandparents’ era, who grew up traditionally on the plains. So it’s not like it’s ancient history—it’s just family history for a lot of us. It’s just that because of how Native American communities were treated, we lost a lot of that food system knowledge. So we just want to be able to do what we can to restore a lot of this really important information that we can all utilize today.

TM: When you were on Pine Ridge, you mentioned your grandfather—were you able to learn about those native, indigenous foods enough so that that was your first exposure to, oh, there’s a different way of eating?

SS: Yeah, and I think a lot of people growing up in tribal communities still maintain some really strong information and knowledge that’s been passed down about wild plants around their area. So we did learn a few species like timpsula, which is a wild prairie turnip, utilizing sage, utilizing chokecherries, and pieces like that. But unfortunately, for a large part of the knowledge, it was just no longer utilized. And that’s what we’re researching and pulling back into now, is just finding a lot of those pieces that people stop utilizing. And we want to get this knowledge and utilization back into especially indigenous communities to help combat those high rates of food diseases that come from poor food access and knowledge.

So there’s just so much more to learn out there and there’s so much to recover. And it’s a pretty awesome path for people in the culinary world because there’s so many exciting flavors and vegetables and proteins to utilize to create a whole bunch of new foods with.

TM: That’s really exciting. It must be very fun to be able to just keep researching and trying all these, and I’m expecting that they’re also delicious.

SS: Yes, very much so!

TM: And interesting, and it’s very satisfying. I’ve read that in 2014, that you started a catering business—and is that Tatanka Truck? Is it a food truck?

SS: We have the food truck, Tatanka Truck, now. We originally started that food truck with the urban Native community—one of the urban Native communities here in Minneapolis called Little Earth. So they purchased the truck and then they hired us to kind of set it up. So we branded it, we hired and we trained everybody and developed a menu. So then we eventually purchased the truck from them. But from the Sioux Chef side of things, we started catering right away just as a way to keep profits coming in so we could keep doing the work that we wanted to do.

But we just became a really unique caterer for the Minneapolis–St. Paul area because we’re really utilizing foods that reflect heavily on the history and the cultures of this area, and we prioritize purchasing from indigenous vendors first and really want to try open up a lot of economic opportunities for those communities to grow more foods that are traditional and healthy to them, and just showcasing people new and traditional ways of utilizing a lot of these foods and flavors to get this health back there out on the tables.

TM: That is so exciting. There’s so many of the reservations that are in food deserts, I understand, was what I read anyways. That’s one of the reasons why it’s been hard to just eat really good food all the time, because of the fact that there’s a long distance to go to buy fresh food. So as you start developing that, and [unclear], are you going to be focusing mostly in the Minneapolis region or in the Great Lakes region?

SS: Our focus is to create this first restaurant that we’re building out here in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area that’ll be more than a restaurant and it’ll also be a center for learning, education, training, testing, things like that. So we want to develop kind of a unique space where people could come and learn from us and develop their own skills. But then we want to help open up small business plan models out on the tribal areas around us, kind of satelliting out, just to influence those regions and get food access to those areas that have a hard time with food access. And just do the same thing, and showcasing people new ways to utilize the traditional foods. And each restaurant becomes slightly unique because each region is slightly unique.

And then we’re hoping to take that whole model and move it around the nation by picking any big city and then replicating that same indigenous food restaurant/training center, and then satelliting around it to create these really unique restaurants. And again, each restaurant becomes unique and each area is unique, but we’re just trying to kind of network and create a web, basically, of indigenous food businesses that will just help crack a lot of the access in education when it comes to working with communities that really need some healthy food around them and it would really benefit from having more knowledge of their traditional food.

(16:58)

TM: If you’re just joining us, you’re listening to Rootstock Radio. I’m Theresa Marquez, and I’m here today with Sean Sherman, and we’re talking about the Native American history, food catering in Minneapolis, about the Sioux Chef, and his upcoming book about Native American food and cuisine. Sean, I’m just really wanting to make sure that our listeners know, if they’re in the Minneapolis region and they want you to cater, how do they reach you?

SS: They can easily just go to our website, which you mentioned before, at Sioux-Chef.com, so S-I-O-U-X dash C-H-E-F.com. And there’s plenty of information there, and there’s a catering tab that people can a quote from us with, and there’s a catering menu up there also. And they’re welcome to visit our new nonprofit that we’re releasing. It’s called NATIFS.org and it stands for North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems. And that’s at N-A-T-I-F-S.org.

TM: I’m interested in the kitchen that you’ve been talking about, where communities use a kitchen to spin off their small business. Is that part of what you had in mind there? Something that would help really multiply the concept and people’s interest in Native American foods?

SS: Yeah, I think shared community kitchen space is really important for people to help develop some of their small ideas, and especially when they don’t have a lot of cash flow to kind of get them moving. And that’s kind of how we had to start too. We had to start just by renting out time at certain kitchens until we were able to grow and move forward and develop the work that we’re doing. So I think as we develop some of these small businesses, that we are hoping that they’ll be able to share their kitchen via rental to some of the small businesses starting up around them to kind of create more and more businesses in that mindset.

TM: I have a crazy question for you, because as I was reading about you, you were saying, you know, “We’re trying to do things without sugar, not the traditional things that you see all the time like fry bread…” And as soon as you said that I kind of like, “Oh, fry bread!” Is there a way to make healthy fry bread? I guess that’s the question I’m trying to get out.

SS: Well, I grew up with fry bread, and we like it too. But the work that we’re doing, since we cut out all influences that were not here before, and utilizing only indigenous ingredients, we’re not using any wheat flour or processed sugar or even dairy or even beef, pork, or chicken. So we’re using a lot of wild game, we use a lot… There’s just so much more, I feel like, that we can utilize, and it’s been a lot of fun. So we create breads out of things like wild rice and out of different tubers and roots, different plants; we use a lot of cornmeal, of course. So we create a lot of really unique pieces with just different stuff.

So, you know, we’re just kind of pushing and testing the limits of what we can do with what’s around us and looking at how simply people processed foods. But also how unique that was and how there’s so much you can do with some of those processes. So we’re finding that we’re able to work around the staple of fry bread, which really just came from the government giving people who were being corralled on reservations subsidies like flour, sugar, lard, and communities who had no ovens or even electricity in some of those times. Fry bread is just something that kind of came around. And it’s integrated into a lot of our communities, but it does not really speak of what the true indigenous food systems were. So we just chose not to bring that into the work model that we’re doing.

TM: I’d love for you to talk a little bit more about your book. And you said it’s coming out in October so it is something for us all to look for. It’s called The Sioux Chef?

SS: Yeah, it’s called the…actually the title is The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen, and that’s being published through the University of Minnesota Press. So I think October 10th or 11th or 12th is the date that it officially releases. And it’s out for presale now, and so people can also find that on our website. But we’re just really exploring how we kind of looked at foods in our regions, especially in this Minnesota–Dakota Territory area, and are doing what we did, and just showcasing people through recipes how simple it is to utilize indigenous-only ingredients to create a lot of fun foods. So I think we have well over a hundred recipes in this book. And it’s our first iteration, and there’ll be a lot of learnings. And we’re looking forward to creating more books that explore other regions of North America in general.

TM: So, you know, how accessible are these for the average person who’s going to buy your cookbook and say, “Oh my gosh, I think I’ll go forage ramps or…” How accessible are some of these ingredients, Sean?

SS: Well, we just really want people to be curious about the nature that’s around them because there’s so much to offer. There’s all sorts of berries and wild onions and wild garlics and wild gingers, and flavors from different various trees, and roots and tubers, and there’s just seed plants and water plants—there’s so much out there. So we want people to really just rethink how much edible vegetation there is around them. And there’s plenty of resources for people to learn about wild foods, botany, and just the plants that are around them and things that they can do. And we want to showcase people how we utilize them.

But we also really believe that wandering aimlessly and foraging isn’t that sustainable. But we believe in permaculture, because we believe we can re-landscape with edibles that are particular to our region that like to grow, and we can grow a ton of food if we just start landscaping smarter and putting up lots of wild edibles in all sorts of places. Like we don’t need gigantic lawns; we could be placing food everywhere, open lots or even golf courses, you know. We can be thinking about the future of just making sure that we have food access all over in all of our communities.

(23:31)

TM: Excellent, thank you, that is such a great point. And one thing that’s part of the Japanese culture is foraging, which is interesting. And you know, the Japanese are some of the healthiest, they’re rated the healthiest people in the world, and they love to forage. And they of course love mushrooms, but they do a lot of foraging. And I think what you were saying is get out there and look to see what kind of resources are around you as far as literature, et cetera, because there’s a lot out there. And if you’re not afraid of the woods and being out in nature, just get out there.

SS: Yeah, and I think people just need to learn, especially because with indigenous communities and foraging, that was a big part, but they were very careful to really treat the plants with a lot of care and to make sure that things were seeding before they were picking them, and returning foods and seeds to areas that they grew well in so they would be creating more and more every year. So instead of just clear-cropping things or pulling up all the ramps by the roots, it’s learning about how to forage sustainably to make sure that there’s more for the future.

TM: I’d love to have you talk a little bit about this Great Lakes Intertribal Food Summit. Something like over 300 people attended. There was quite a few tribes, and it sounded to me like you were very active in that. Can you describe that to us a little bit? It just seems so exciting and interesting.

SS: Actually I sent three of my team members out there because, myself, I had events in Europe during that exact same time. So I was with Nordic Food Lab in Denmark at the time of that event in Michigan. But we’ve been working really closely with the organizers of that Great Lakes Summit, and we do a few events throughout the year with a lot of those same players. And it’s just really fun to gather a bunch of people from around the U.S. and Canada together to really reflect and to create and talk about where we’re going with a lot of this, and really be a part of this kind of movement that’s been happening. So it’s been really exciting to explore and to learn and to share with other chefs and like-minded people from all over the place.

TM: It just sounds wonderful. Was that a first summit and will you plan to do it again?

SS: That was not their first summit, and they are organizing more every year. And we’re a part of quite a few different summits and events like that, so we stay pretty busy, and we’re seeing a lot more bubble up. So there’s going to be all sorts of, more and more fun events like this continuing to happen across the U.S.

TM: Well, you know, now that you’ve got my curiosity piqued, what were you doing at the Nordic Food Lab? Do you mind if I ask?

SS: We were actually with a few different chefs from around the world. So Nordic Food Lab was there; Alìcia Foundation, which is a test kitchen in Barcelona, which kind of stemmed from Ferran Adrià’s El Bulli; there was a really talented chef from South Africa, one from Montreal, and ourselves. And we put on this dinner that focused on chefs’ interpretations of food in 50 years through utopian or dystopian visions. So we put on a six-course dinner with each course reflecting on our own experiences of how we can combat all sorts of issues that we’re going to come up with in the next 50 years when it comes to food sourcing and availability.

TM: Wow, that’s pretty remarkable that someone had a vision to bring people together to dive into that topic.

SS: Well, we’re going to have to have those conversations because they’re going to keep coming up faster and faster.

TM: For our listeners, there is the website—

SS: Sioux-Chef.com, so S-I-O-U-X dash chef dot com.

TM: Right, and there’s some links to articles on Sean, and one of them was in the New York Times, and there’s some beautiful photos of wild harvesting, for those who are interested in seeing just how beautiful it looks to just be out wandering around and picking, looking for things and harvesting them.

SS: Yeah, there’s so much to offer in all areas of everywhere. So it’s a great education to have.

TM: When you look to see what the history of food is and just how healthy we were—before we gave up our responsibility for our food, we were much healthier. And certainly I see that many of the—you, Sean, and many of the Native Americans are really discovering, “Oh, let’s start feeding ourselves again.” So I’m very…it’s inspiration to hear all the things that you’re doing to both be modeling that as well as educating that. So I just want to thank you for all that great work that you’re doing.

And also, thank you for being with us on Rootstock Radio. It’s just been very good, and I’m wishing you much luck and really hoping to follow your new restaurant and your new endeavor, and can hardly wait to see your cookbook.

SS: Thank you.